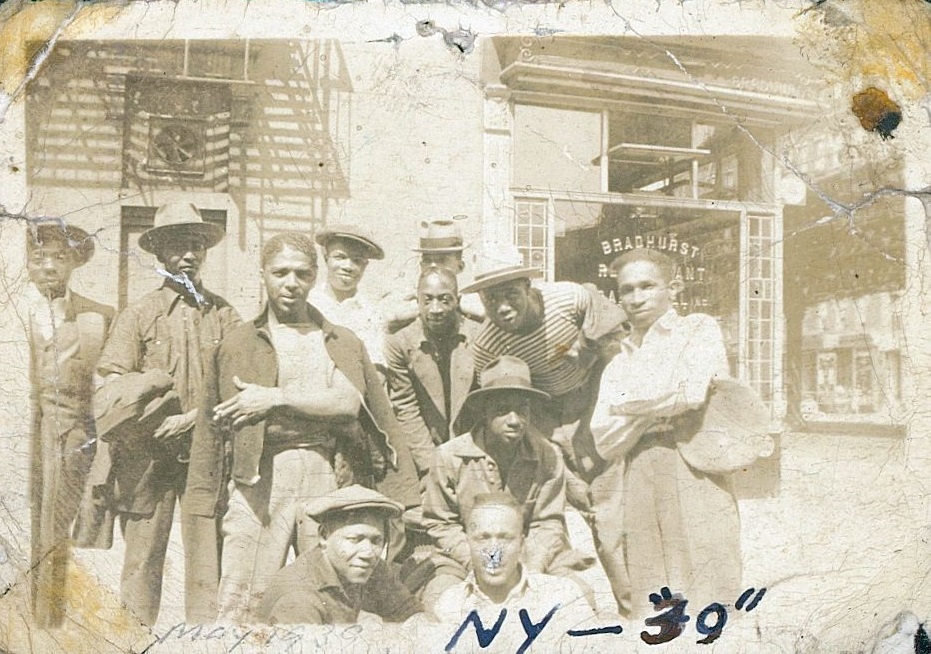

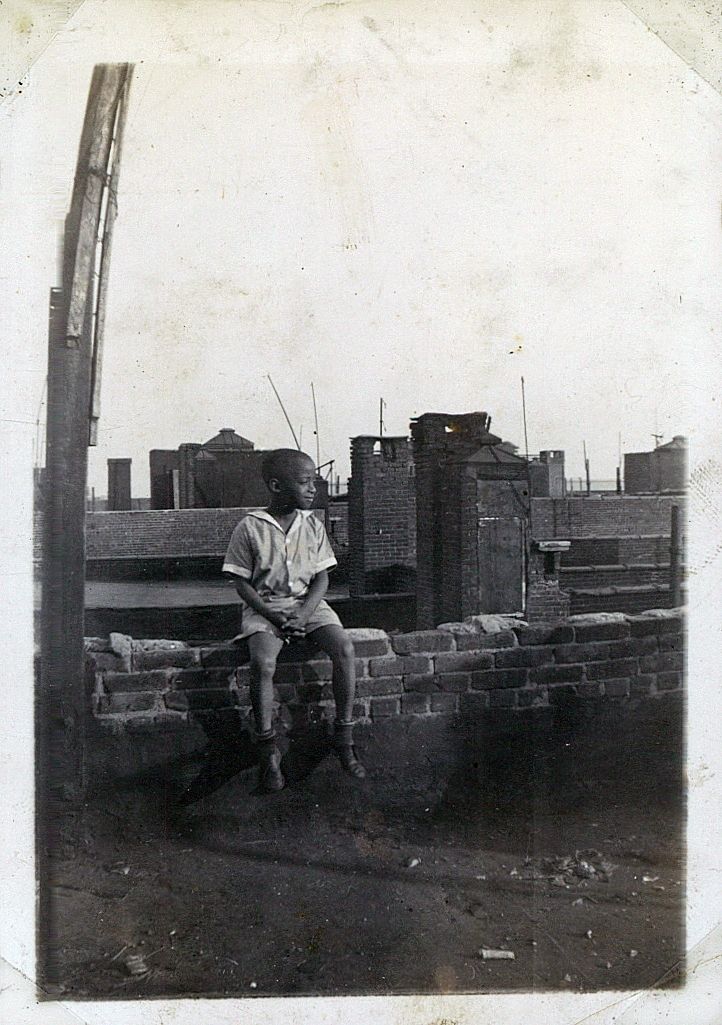

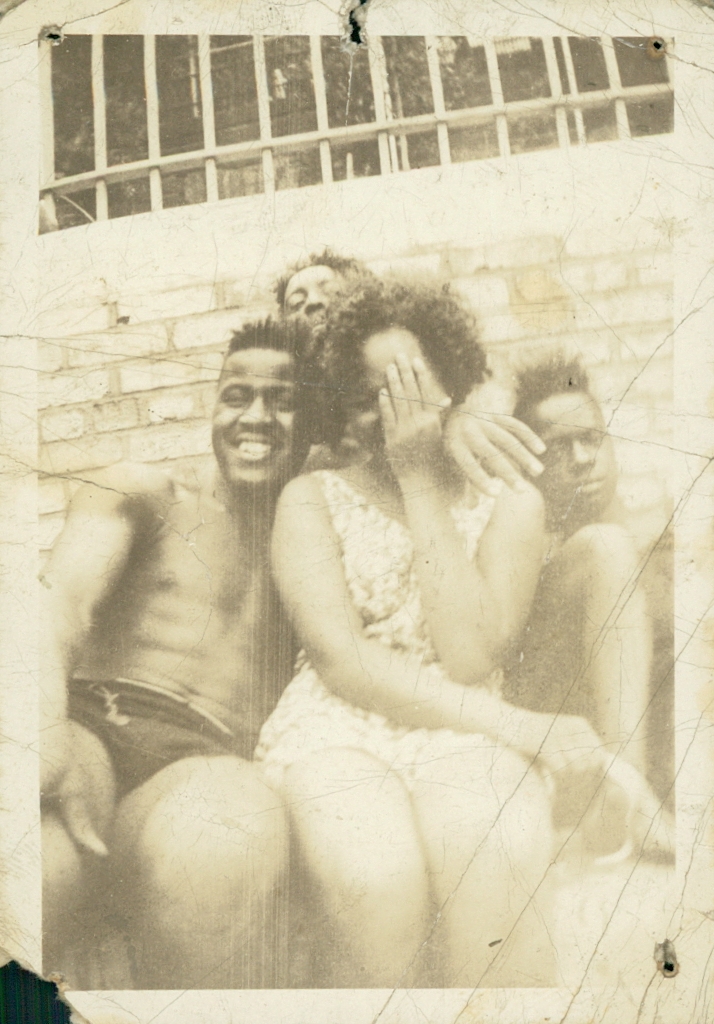

Places

Curator's Notes:

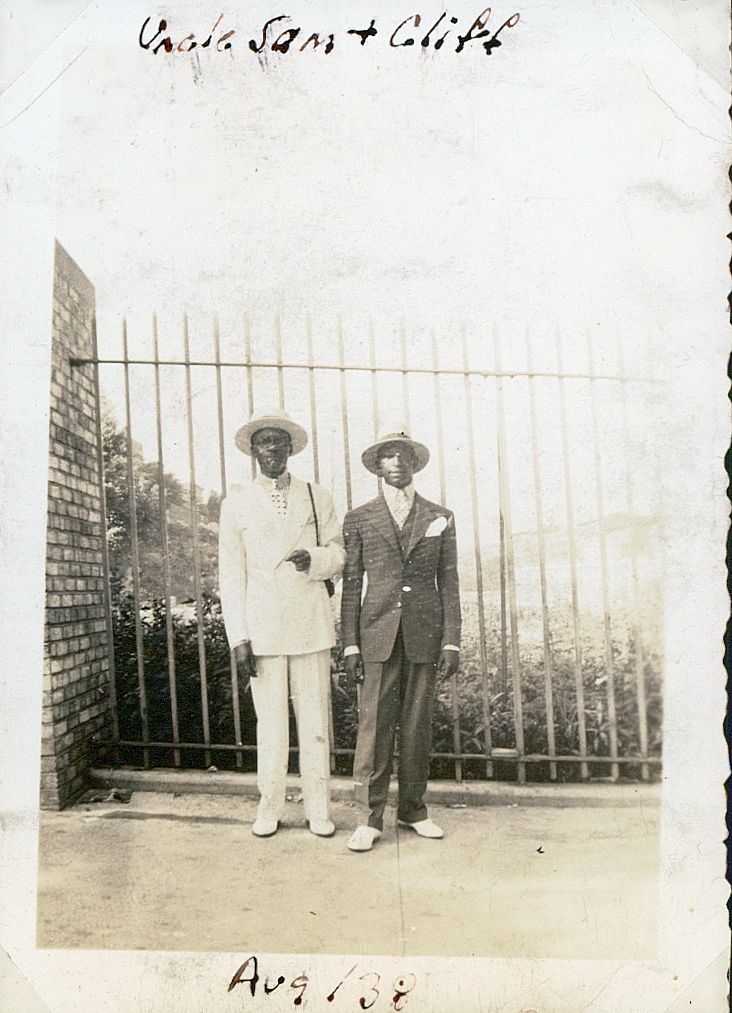

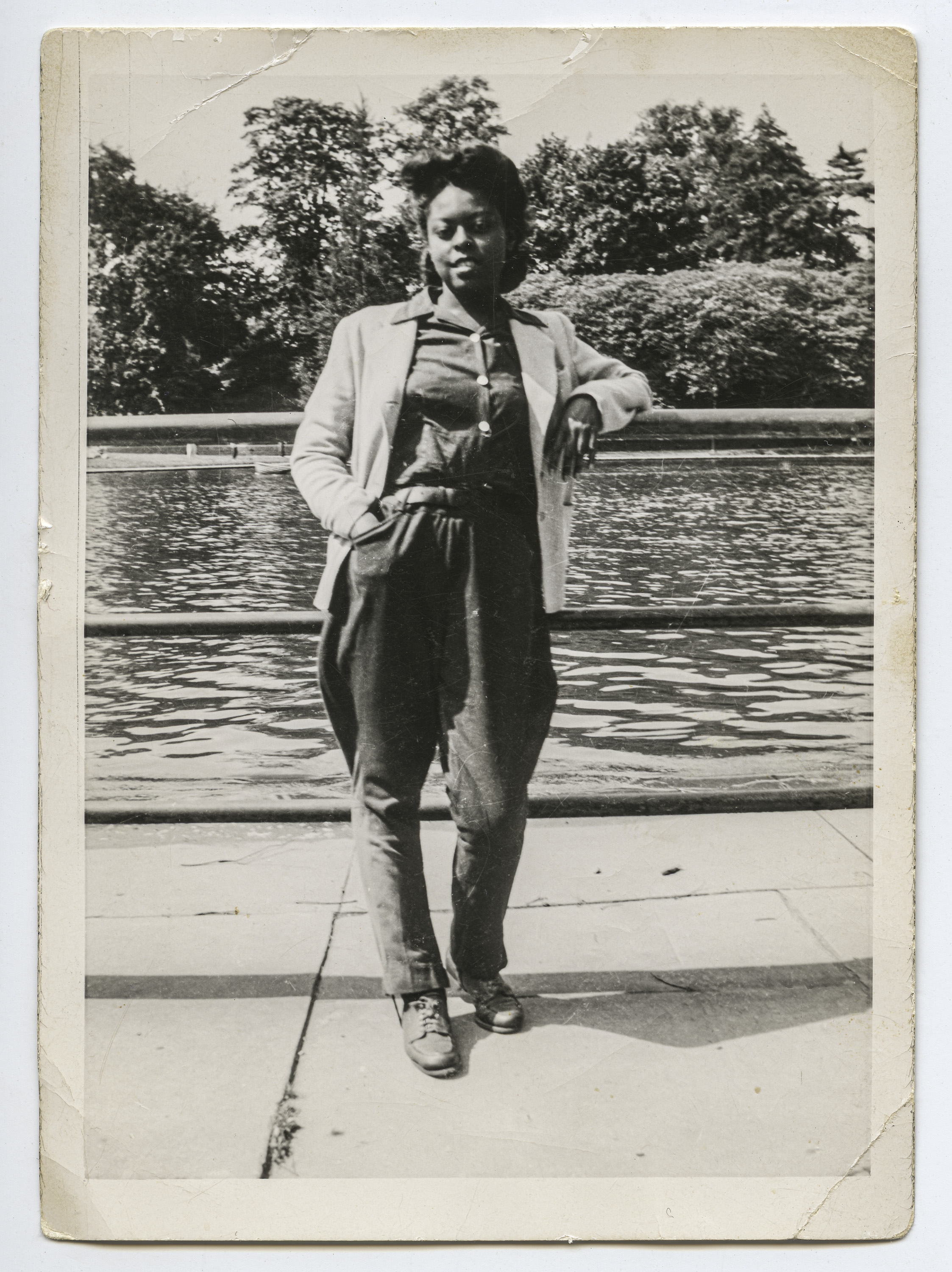

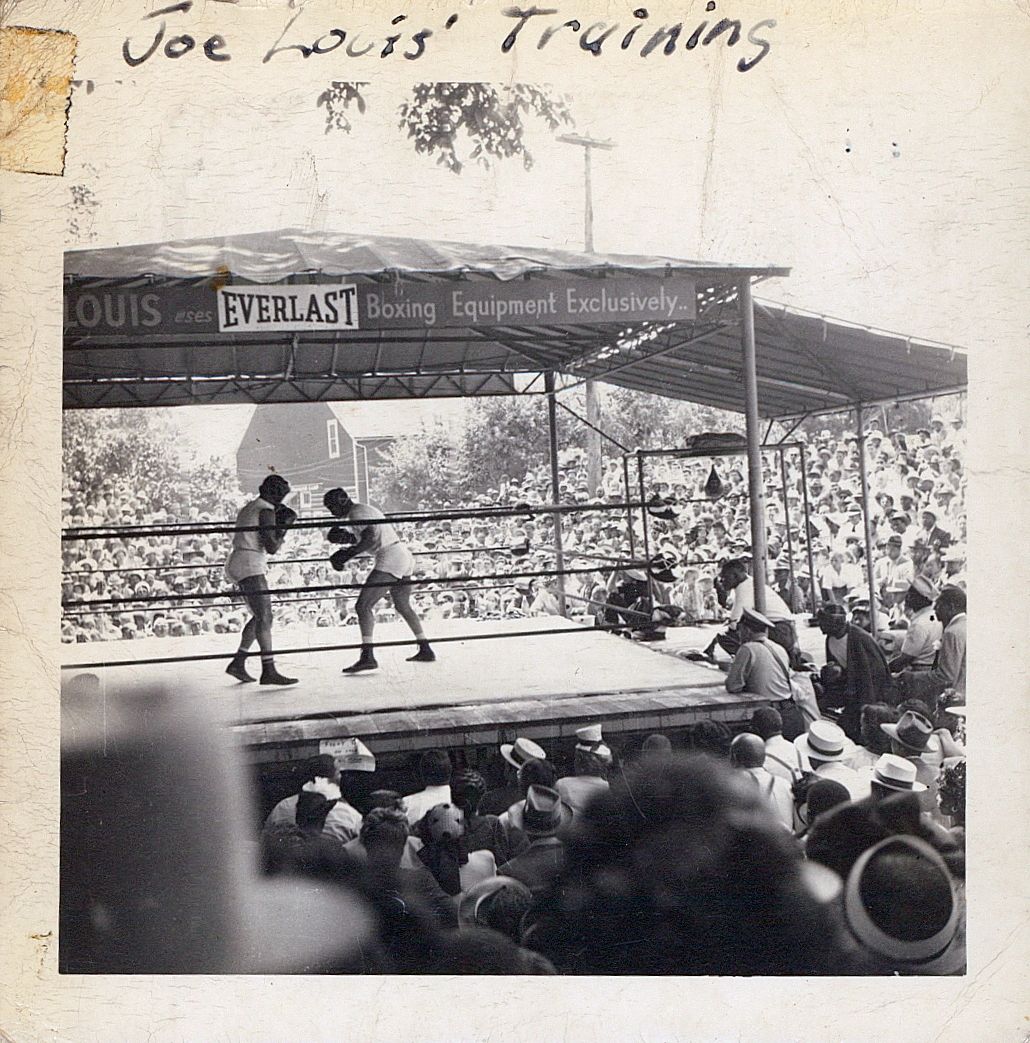

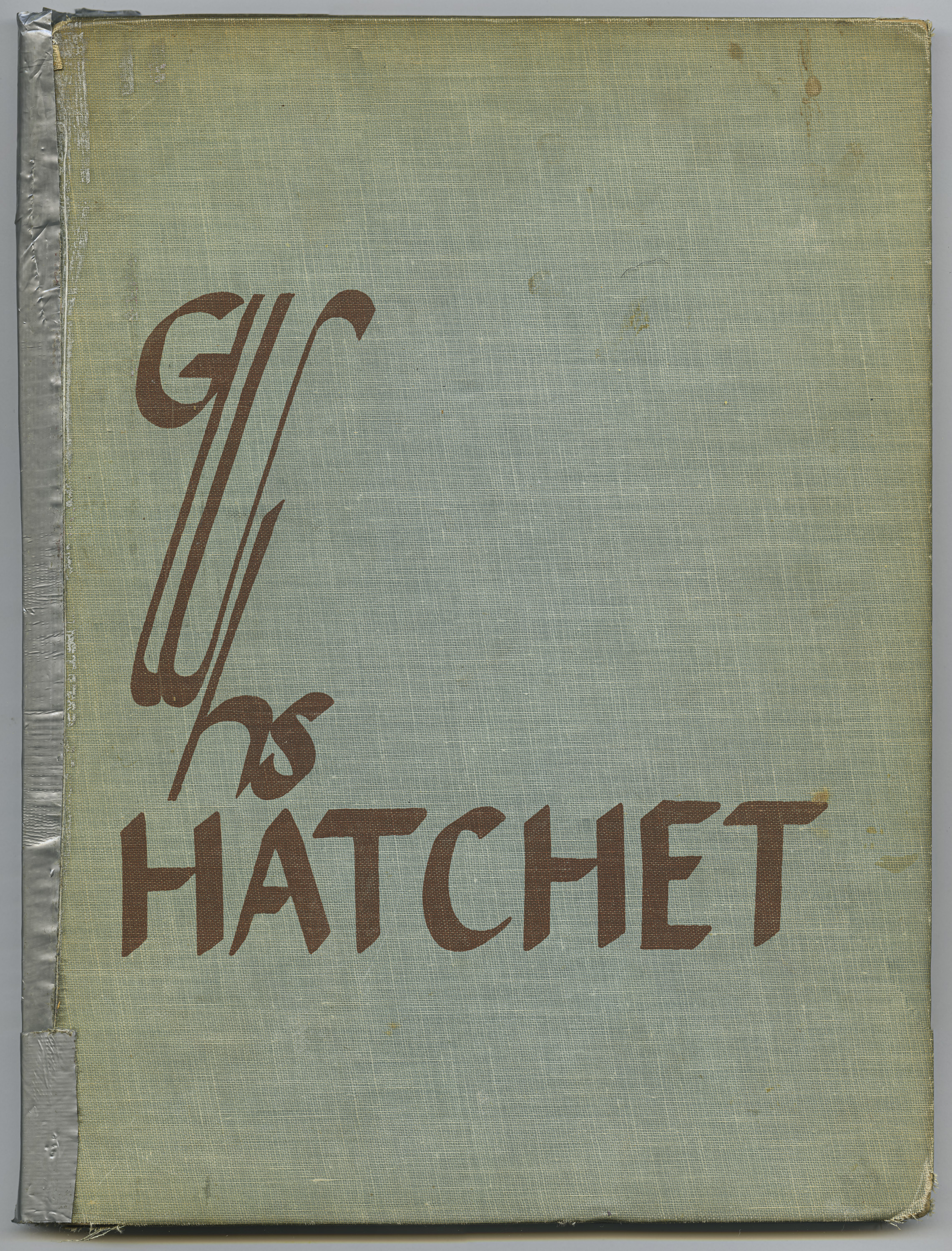

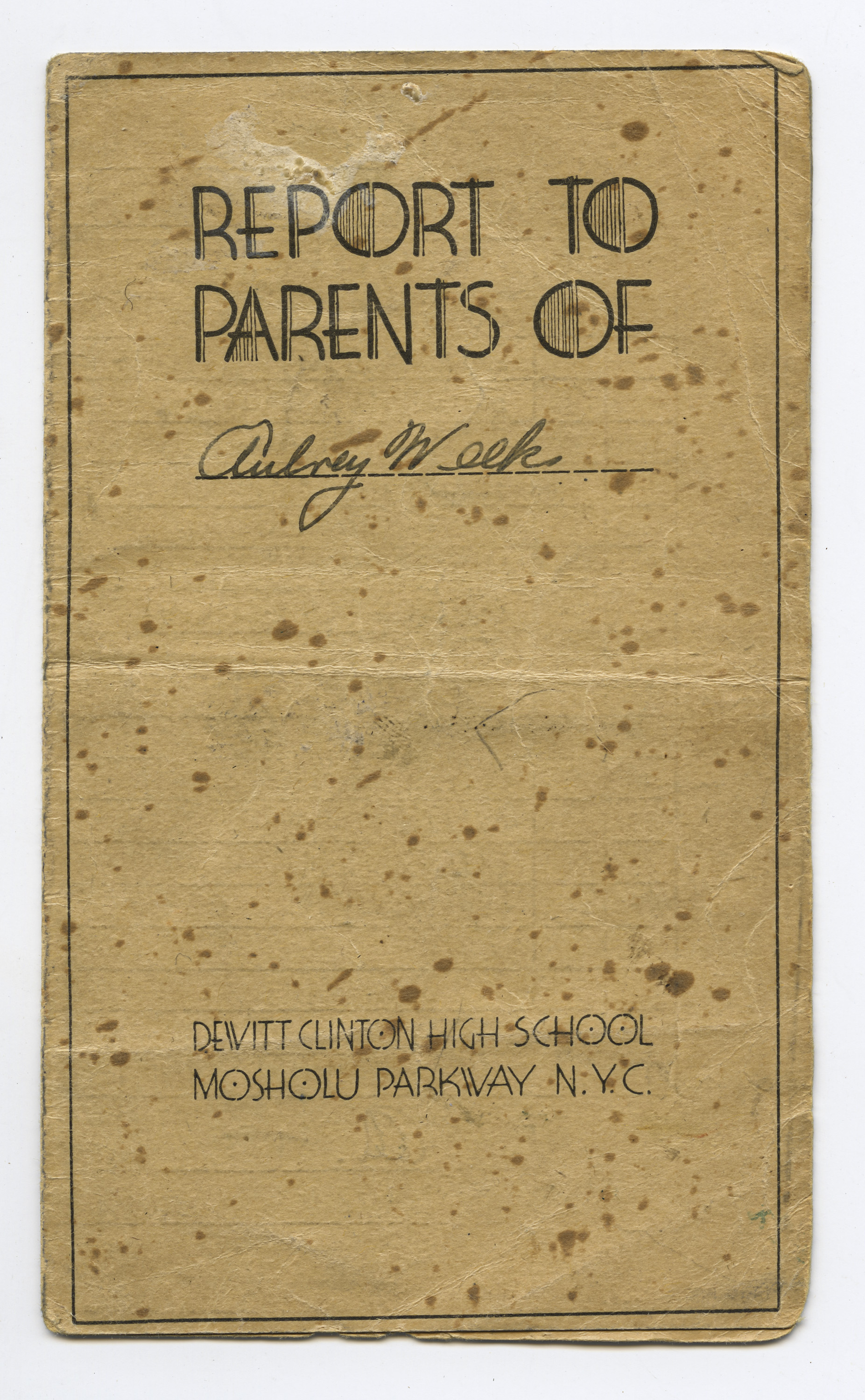

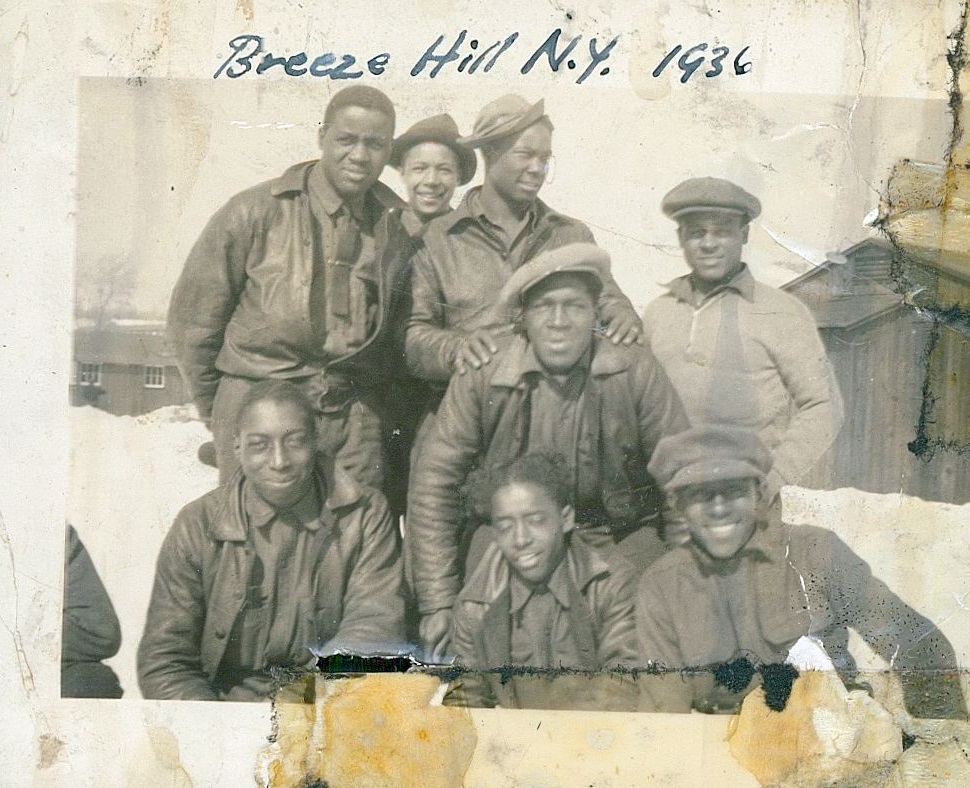

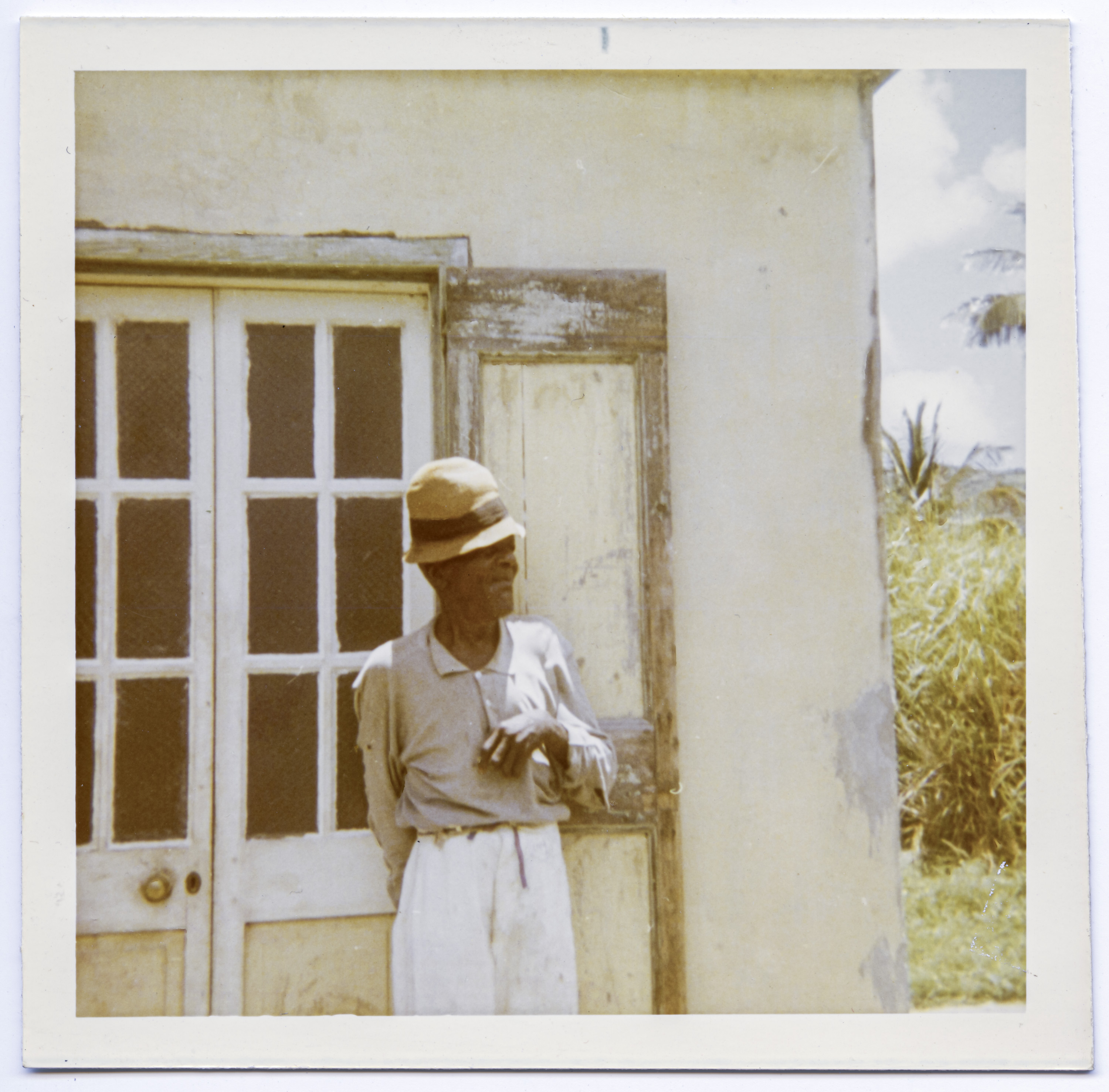

Place, as an identifiable physical location and as an abstract idea (i.e. space), is significant to the African diaspora. It shows up in the “placelessness” that is fundamental to the Diaspora itself — the way we were taken from Africa means we have no specific place to call an ancestral home on the continent; and in the Americas, we were not brought here to survive and are always reminded we don't belong. Related to that “not belonging” is the ways we have been/can only be in certain places — the back of the bus; within a real estate red line; in the hood, favela, or barrio; but not in the suburb, etc. And if we don't know our place (Emmet Till) or are out of place (Trayvon Martin), we lose our lives. Then, there is the way we use place, blurring the ideas of public and private space, like getting cornrows on a front porch or creating safe places for ourselves like the Clove Valley Dude Ranch that was in the Green Book. We also give place a new meaning, such as how Black people, like Umi's great grandparents from the Caribbean and Black people from the US South, turned a parcel of the dispossessed land of the Manhattans and Lenape, named Harlem by Dutch colonists, into a center of the [Black] Universe.